In this episode we look at five famous Tudor portraits, and the message they were sending. A picture is worth a thousand words, right? What message do you get from these images? Leave a comment and let me know! For those who prefer to read, the transcript is after the links.

Remember that you can support the show in a number of ways. You can leave a rating on iTunes which is a huge help. You can also become a patron for as little as $1/episode on Patreon.

And so now, on to the show!

Web Sites

http://www.marileecody.com/eliz1-images.html

The Family of Henry VIII

http://www.historytoday.com/suzannah-lipscomb/all-king%E2%80%99s-fools

Elizabeth I

A great web resource listing many many portraits of Elizabeth, and a bit of their stories

http://www.marileecody.com/eliz1-images.html

Books:

Cult of Elizabeth: Elizabethan Portraiture and Pageantry by Roy Strong

Elizabeth I’s coronation portrait, which is incredibly similar to that of Richard II, one of the earliest portraits of a monarch

Video: Art in Context: Lisa Ford on the “Allegory of the Tudor Succession: The Family of Henry VIII”

Now that we’ve had that brief entertainment and hilarity, here’s some more serious videos.

TRANSCRIPT

(Remember if you like this program that you can support it by leaving a rating on iTunes, or becoming a patron on Patreon for as little as $1/episode. And thanks!)

Hello, and welcome to Episode Thirty Eight of the Renaissance English History Podcast: Portraits and Propaganda. I’m your host, Heather Teysko, and I’m a storyteller who makes history accessible because I believe it’s a pathway to understanding who we are and our place in the universe.

This week I’m going to talk about art. I did an episode a few years ago about visual arts in Renaissance England, but I really want to do more with it. I’m tracking down some experts to interview, but in the meantime, I want to explore my own personal interest, which is in the almost modern use of visual arts to forward a particular message about the Tudors – ie propaganda. So what I’m going to do for this episode is look at five very famous Tudor portraits, and examine the background behind each of them, what they were saying about the subject, and why they are important. You will most likely want to check out the show notes to see the actual images themselves, though I’ll try to describe them, so those of you who read a lot about this period will probably be familiar with them.

The first one I want to look at is the famous 1537 portrait of Henry VIII as part of the Whitehall mural by Hans Holbein. Actually, the bulk of these images will be by Holbein because he was the go-to-guy for Royal portraits, but the one I’m thinking of in particular is the one that shows the family of Henry VIII, with his wife Jane Seymore, and his parents Henry VII and Elizabeth of York.

So what was happening in England in 1537 when this was commissioned? The year before Henry had dispensed with Anne Boleyn, executing her on trumped up charges of adultery and witchcraft. The Pilgrimage of Grace had threatened the stability of northern England when tens of thousands of people protested the King’s separation from Rome and dismanetling of the monastaries. And, in early 1536, before Anne had died, Henry suffered from a horrible jousting accident that would forever leave him injured, and surely had him scared and thinking about his own mortality. He still had no male heir, and what’s even worse, he had been on the throne for over 25 years. Even worse, the standard attitude towards a woman’s adultery in Renaissance England was that the husband must not be able to keep his wife happy, which is why she had to go elsewhere. Adultery on the part of a woman was almost as embarrassing for the husband as the wife. And so, here’s Henry, his reign threatened, his wife executed, his leg still sore, and no male heir.

He was just finishing up the building of Whitehall Palace, which was along the river, stretching from Charing Cross to Westminster. Holbein was commissioned to create a mural that would decorate the privy chamber. It was a life sized painting, measuring 3 meters by 4. That’s like 9 feet by 12 feet. A huge painting that would dominate the chamber. It would include Henry and his parents, and his current queen, all standing around a piece of marble inscribed with a message about the Tudor dynasty.

There, front and center, was a life sized portrait of Henry, looking directly at the viewer, in all his glory, designed to create awe in anyone who came close to it. There were jewels in his furs, in his cap, luxurious clothing showing how wealthy he was, and then there was the codpiece. This is the pose we will forever associate with Henry. Wide stance, feet apart, hands on hips, looking directly at us, daring us to question his supremacy, with his codpiece front and center, showing us what a virile man he is. Any woman who would go elsewhere had to be crazy, it yelled. Want to laugh about him behind his back? Yeah, well, look at that monster. Basically, the whole portrait was designed to have us see what a man he was. This was the first time a portrait had been used in this way, and people were literally struck dumb when they encountered it. No one had ever seen anything like it. Workers were caught off guard, and bowed to it. At first people thought it was really the King. Any nobles who came into the privvy chamber, nobles who might be tempted to plot and rebel against the Tudors, who might still consider them Welsh upstarts even 50 years after Bosworth Field, would think twice about taking any rebellious actions when they saw the might and strength of their king like this.

The pose of the portrait itself was considered vulgar in the courts at Europe. Apparently it was also considered bad form to depict royals full face, and in Holbein’s original design Henry appeared ¾ face. The change was probably something the King asked for.

Karel van Mander, writing in the early 17th century commented that as Henry,

“stood there, majestic in his splendour, [he] was so lifelike that the spectator felt abashed, annihilated in his presence”.

And the truth? At the age of 45 Henry was on the brink of old age. The athletic youth who had revelled in tiltyard sports was a figure of the past. Thrombosed legs were causing him increasing pain and would soon turn him into a semi-invalid. He was becoming fat and unwieldy. Those slender legs were, in reality, bandaged to cover open sores issuing stinking pus.

In 1537, Henry VIII, far from being the man he wished others to see, was insecure. The past was a depressing panorama of expensive and inglorious military adventures; of twenty-eight years of married life without a son to show for them. The present was a skin-of-the-teeth survival from defeat at the hands of unruly subjects; of continued threat from people who regarded him as a tyrant. The future was probably short and might well witness the end of the Tudor dynasty.

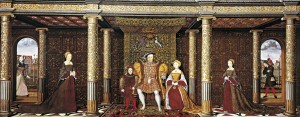

Next up, we’ve got the Family of Henry VIII. That lovely portrait from 1545 that shows Henry with his son Edward, his favorite wife Jane Seymore, and his two daughters. There are two other mysterious figures in the background, and they are in fact Will Sommers, Henry VIII’s fool, and Jane the Fool, Fool to Anne Boleyn, Mary Tudor, and Katherine Parr. They are in the background, outside archways that look out over London, showing the King’s garden, outlined in the Tudor colors of green and white, and show the scenery of London with parts of Westminster Abbey and the King’s great tennis court just barely visible. The artist is unknown, though there is a strong influence of Holbein. The painting was originally displayed in the Presence Chamber at Whitehall Palace.

So what was happening in this time that would have influenced this painting? Well, for one, Jane Seymore had been dead for years, and henry was on his third wife after her, Katherine Parr. But let’s look at what else was going on in the life of Henry. To start with, he was getting very old, and was pretty miserable. His leg was still injured from his jousting accident, and there are stories of how Katherine had the unenviable job of having to be his nursemaid. We can only imagine how uncomfortable this would have been for him. There’s none of this evidenced in the painting though. Just nice elegant shapely legs outlined in white hose.

In 1545 Henry’s kingdom was threatened when the French sent an Armada larger than the Spanish Armada would be a generation later. 30,000 soldiers in more than 200 ships. Henry was constantly on the defensive after his break with Rome and dissolving the monastaries. All the good Catholic rulers of Europe saw an opportunity to get on the Pope’s good side, and perhaps enjoy some extra purgatory kudo’s, and gain some land and prestige in the process, and England was constantly on the lookout for invading forces. If you haven’t yet listened to my episode on Henry’s navy, you can get more detail on the defensive buildup during this time in that show. It was during the battle with the French armada that Henry lost one of his earliest warships, the Mary Rose.

So here’s Henry. He’s old. His son is still a child. He’s obese. He has a leg injury that leaks pus.

His empire is under constant threat. He just lost a favorite ship.

But that’s not what he wants to show people who have entered his Presence Chamber. He wants to show the succession is assured. He wants to show his son, strong and robust like his father (when in fact Edward would die a teenager). He wants to show his daughters as part of the line of succession in case something would happen to his son. He wants to show a happy family with luxurious surroundings. Yes, I may have dissolved the monasteries and you might not like that, it says, but just look at how wealthy I am now. Look at the tapestries on the walls, the carvings, the rug on which I put my kingly feet. Look at my jewels. And of course my codpiece. Look, and weep. Because I am mighty King Henry. You think you can invade my country? I stood up to the Pope, to everlasting damnation, to God Himself, thank you very much. I have no time for your hollow threats and your plotting and intrigue. Just look at this dynasty. Look at how secure we are. We don’t give a damn about your Pope. We have tennis courts! And shapely legs!

Indeed, this portrait of the family makes everything look so hunky dory that you would have no idea just what a crappy time it was for Henry. Which is, of course, how he would have wanted it.

Now, let’s move on from Henry and his gross leg wound, shall we? Onwards to Elizabeth, who is, in so many respects, her father’s daughter, and she could have taught a thing or two to branding experts on Madison Avenue. There are so many portraits of the Queen; one thing that differentiated her from other monarchs of the time is that she never granted the exclusive right to paint her image to any one person, and so there are paintings of her from many different artists. She did, however, keep close control over what the images of her that were released looked like, and as such, the imagery and messages in her portraits helped build this cult of Gloriana that we still associate with her. So painters worked from face patterns – she would sit for one artist, and then they would use that painting to make patterns and copies so other artists could do their portraits. I could do a year’s worth of podcasts just on the portraits of Elizabeth, and sadly, I just don’t have the time to go into them all here. But we’re going to look at three. One as princess, and two as Queen, and look at the messages that she was sending to her court, her subjects, and history.

First off, why so many portraits of Elizabeth? Portraits were commissioned by the government as gifts to foreign monarchs and to show to prospective suitors – and because Elizabeth stretched out marriage negotiations for so long, there was a lot of buzz with portraits. Courtiers also commissioned paintings to demonstrate their devotion to the queen. The long galleries in country homes like Hardwick Hall, of which we’ve spoken about before, would have been full of portraits of monarchs and nobility.

So, let’s look at a portrait of Elizabeth as Princess. It’s one of the earliest portraits of Elizabeth, painted when she would have been about 13 years old. It’s attributed to William Scrots, an artist from the Netherlands who painted for Henry VIII after about 1545. Henry probably commissioned the portrait, and it’s first recorded in an inventory for her half brother Edward VI, where it is described as ‘the picture of the Ladye Elizabeth her grace with a booke in her hande her gowne like crymsen clothe’.

In this pose, Elizabeth looks demure and pious, with two books included, showing her to be educated and studious. The smaller book probably represents the New Testament, and the larger book to the Old Testament. This will be one of the simplest portrait we see of her; and is contrasted to the theater and pageantry of later portraits. The early portraits as Queen kept this feeling of serious pious devotion, which is no surprise considering many still viewed Elizabeth as illegitmate, she had yet to prove herself on the world stage, and she was still finding her feet as monarch. The first portrait of her in her coronation robes is actually modeled after a similar portrait of Richard II, only the second portrait of an English monarch that we have. She sits holding her scepter, with her golden red hair flowing down her back, which is covered with jeweled robes, looking serious, and not at all like an illigetimate princess who would be excommunicated by the Pope just over a decade later.

As time went on and Elizabeth found her feet as a monarch, surrounded herself by her able advisors, and brought some stability to England, the portraits of her became more theatrical, and used allegory to tell the story of her succession and the Tudor dynasty, which was now so firmly entrenched.

One of these portraits actually has two versions. The Family of Henry VIII, An Allegory of Tudor Succession will be recognizable to those of you who had the Advent Calendar in December, as one of the versions was the image I used. Obviously this portrait isn’t an actual statement of fact. Henry, Mary and Edward are all pictured, as is a grown Elizabeth, which would have been a physical impossibility, as they would have all been dead by the time she was this old. But it tells the story of Henry VIII passing the throne on to the Protestant Edward, and showing by his look and the turn of his hand towards Elizabeth, who would carry on the Protestant reformation in England. Mary and her husband Phillip II of Spain are pictured on Henry’s right side, along with Mars, the God of War. This is a powerful statement about how Elizabeth saw her family.

She is on the right, on Henry’s side, holding the hand of Peace (who is stomping on a sword) and followed by Plenty, holding a cornucopia. Henry VIII sits on the throne, passing the sword of Justice to Edward. Mary and Phillip are both painted in darker colors, while Elizabeth, Henry and Edward are all painted in brighter colors, showing that they stood in the light of truth.

The painting was first commissioned around 1572 when Elizabeth was beginning to see herself as the culmination of the Tudor Dynasty, and it was a gift to her advisor Francis Walsingham. Of course 1572 was also when the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of Protestants happened in France, which Walsingham witnessed and survived, and it may have been a gift to remind him of the rightness of the Protestant cause. It was repainted later, after the defeat of the Spanish Armada, and in the two different portraits everything looks pretty much the same, except Elizabeth has an updated dress and looks a bit older. The second commissioning may have been done to celebrate the victory over the Spanish Armada.

So let’s talk about the Armada now, shall we? One of the most iconic portraits of Elizabeth as Queen is the famous Armada Portrait, painted in 1588 after the defeat of the Spanish Armada. It shows Elizabeth surrounded by the symbols of imperialism against a backdrop showing the defeat of the mighty armada. It is life-sized, and would have been awe inspiring, just like Henry’s portrait.

The background shows the two different stages in the defeat – first, when the English fire ships drifted in to the Spanish area and threatened their ships. Second, when the Spanish ships are driven onto the coast when the winds were threatening them. Some also say that this shows Elizabeth turning her back on the dark while the sun shines in the direction of her gaze.

Her hand rests on a globe, and her fingers are on the America’s, specifically south America, which had been dominated by the Spanish. This shows the plans for imperialist expansion and exploratoin into the America’s.

Art historians have pointed out the geometry of the painting, with the repeating patterns of circles and arches in the crown, the globe, and the sleeves, ruff, and gown worn by the queen. They also contrast the imperial figure of the Virgin Queen wearing the large pearl symbolizing chastity suspended from her bodice and the mermaid carved on the chair of state, representing female wiles luring sailors to their doom.

So, quite a bit going on in that one portrait.

There are three surviving versions of the portrait in addition to several derivative portraits. There is one at Woburn Abbey

The version in the National Portrait Gallery, London, which has been cut down at both sides leaving just a portrait of the queen.

The version owned by the Tyrwhitt-Drake family, which may have been commissioned by Sir Francis Drake, was first recorded in 1775. Scholars agree that this version is by a different hand.

The first two portraits were formerly attributed to Elizabeth’s Serjeant Painter George Gower, but curators at the National Portrait Gallery now believe that all three versions were created in separate workshops, and assign the attributions to “an unknown English artist”

So, for the book recommendation. I don’t have a book recommendation for this episode, BUT, I’m giving away a Tudor Book Bundle of five really great books, some of which have been recommended in the past. Check it out and enter to win on the website at https://www.englandcast.com. I’ll put a link up on the site and facebook page, which again is facebook.com/englandcast, where you can again contact me, send me show ideas, or just say nice things. And again, you can get all the book recommendations, show notes, sign up for the mailing list, etc at https://www.englandcast.com.

Remember if you like this program that you can support it by leaving a rating on iTunes, or becoming a patron on Patreon for as little as $1/episode. And thanks!